US-China Trade War on Rare-Earth Minerals: What this means for Deep-Sea Mining

In response to Donald Trump’s escalating tariffs, China has retaliated by placing export restrictions on rare earth elements. China produces around 90% of the world's rare earth minerals, and is the worlds leading refiner of these elements, which are used across the defense, electric vehicle, energy and electronics industries. Rare-earth minerals are at the heart of the coming energy transition.

But if China decides to further choke off its supply, the ripple effects will negatively impact many industries. The U.S. simply does not have the means to create the materials it needs to create the devices it survives on.

The White House clearly understands the importance of free-trade in relation to these minerals; as it exempted critical minerals from its tariffs regime this month. But that did not stop China from issuing export controls on seven kinds of rare earth elements, to all countries, on Friday. The decision is not a ban, but it does give Beijing oversight and control, and is clearly a retaliatory tool on the Trump tariffs.

How could this impact deep-sea mining?

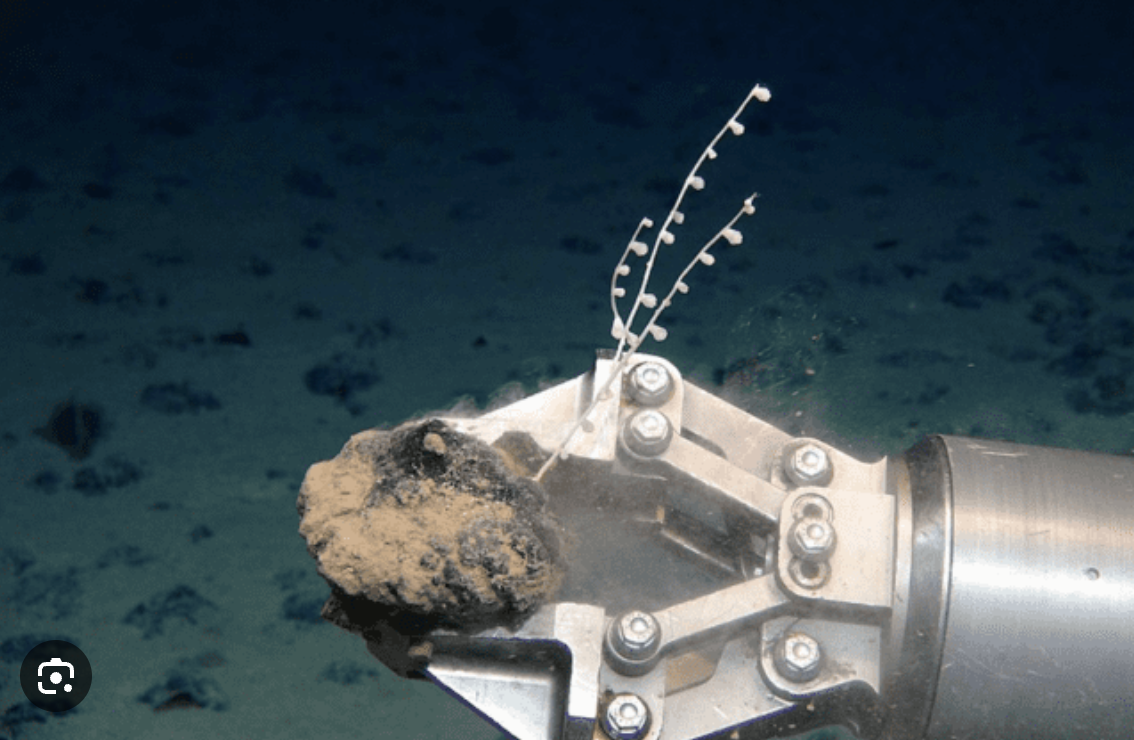

Trump’s tariffs, and the ensuring trade war, could, and likely will, force American companies to build up supply chain resilience to wean themselves off of Chinese rare-earth reliance. For the United States, the stakes are higher than ever, and as such, Trump's government is searching for alternative ways to regain control. One of these methods is deep-sea mining.

The White House is weighing an executive order that would fast-track permitting for deep-sea mining in international waters and let mining companies bypass a United Nations-backed review process. This order will likely stipulate that the U.S. aims to exercise its rights to extract critical minerals on the ocean's floor, and let miners bypass the International Seabed Authority (ISA), instead allowing them to seek a permit to mine through NOAA.

Despite operating in international waters, the domestic law the U.S. will rely on for deep-sea mining permitting (Deep Seabed Hard Mineral Resources Act of 1980 (DSHMRA)) allows the U.S. to assert a unilateral regulatory framework for its nationals engaging in seabed mining, which effectively creates a parallel system to the ISA's international regime.

DSHMRA mandates environmental impact assessments and sets basic guidelines to prevent “serious harm” to the marine environment—but its standards are far less rigorous than those emerging from ISA protocols today.

If this framework was implemented, it would send a strong signal to American companies and international competitors that the U.S. is prepared to exploit seabed resources independently. It would also very likely intensify the race for deep-sea resources, as countries like China, Russia, and Norway also invest in seabed exploration and extraction.

Bilateral mining outside of the realm of International bodies could set a precedent for others to follow suit—potentially leading to a race to the bottom where nations ignore international law in favor of national gain. Besides, this could weaken the ISA’s legitimacy, frustrates global coordination, and could push the system into fragmentation—similar to what’s happened in some other areas of international law when enforcement mechanisms were ignored.

Because the U.S. never ratified UNCLOS (U.N. Convention of the Law of Sea), it cannot sponsor companies through the ISA. DSHMRA serves as a domestic workaround, allowing U.S. companies to operate outside the ISA regime while still enjoying a legal structure.

Furthermore, as the United States has not ratified UNCLOS, it is not legally bound by the treaty’s dispute resolution mechanisms, including the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS). Thus ITLOS cannot exercise jurisdiction over the United States or its entities in a direct case brought by another state under UNCLOS, meaning wronged states do not have an enforcement mechanism to protect their common heritage in the deep-sea should the U.S. begin mining.

For those of us worried about the environmental impacts of irresponsibly mining the deep sea, these are dire news.

However, the fight is still not lost. For us inside of the United States, there are several things we can do:

- Require comprehensive NEPA reviews:

Even though DSHMRA permits NOAA to issue mining licenses, any federal action that may significantly affect the environment must comply with the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). It is our legal right to demand comprehensive Environmental Impact Statements for any exploration or mining activity. Furthermore, we can challenge insufficient environmental review or failure to consider alternatives and cumulative impacts. We know that the environmental impacts of dee-sea mining are not well known.

- Invoke the Endangered Species Act (ESA) and Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA)

Attorneys can file claims under the ESA or MMPA to require biological assessments of deep-sea mining , and possibly incidental take permits. There is a strong argument that mining activities may jeopardize endangered species or critical habitat.

- Shape the Narrative around Deep-Sea Mining Through Strategic Advocacy and Public Pressure

Attorneys now, more than ever, should seek collaboration with scientists, NGOs, and Indigenous leaders and join our coalitions.We can mount political or legal challenges, utilizing state Attorney Generals to mount pressure. While we may feel powerless to stop unilateral deep-sea mining alone, we can absolutely slow it down, raise the costs, spotlight the harms, and shape the legal and ethical framework under which it will be scrutinized.